When I moved from Chicago to Champaign, Illinois, in the fall of 2005 I noticed the pervasive use of the term "heartland" in local businesses. There are banks, heating and cooling companies, burger shacks, etc., all with some version of Heartland in their name. Chicago has its lefty Heartland Cafe and a few other similarly named businesses and organizations. But nothing like downstate. Why all this claiming of the heartland, I wondered, and what does it mean?

When I moved from Chicago to Champaign, Illinois, in the fall of 2005 I noticed the pervasive use of the term "heartland" in local businesses. There are banks, heating and cooling companies, burger shacks, etc., all with some version of Heartland in their name. Chicago has its lefty Heartland Cafe and a few other similarly named businesses and organizations. But nothing like downstate. Why all this claiming of the heartland, I wondered, and what does it mean?For about a year I've been thinking about a project that would answer these questions.

My working thesis is in two parts, one about timing, the other about meaning. First, although a term of long-standing, the use of "heartland" to describe the Midwest grew as the region was heading into industrial decline after 1973 in the face of a new wave of global economic integration. Second, "heartland," is a term of reaction and forgetting. It recasts the "rustbelt" (the image of urban decay) into a bucolic, racially homogeneous (white), politically and socially conservative small-town region.

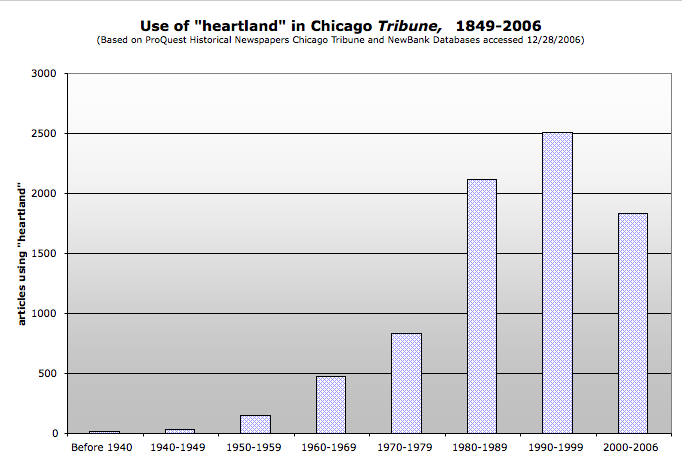

After talking to Jim Akerman and Bob Karrow at the Newberry Library, specialists in maps and vernacular geography, I decided to track the use of "heartland" in historical newspapers. Thanks to the digitized databases, this is just a matter of an afternoon's work. The chart at the head of this post shows the results of that work (if you click on the image you can see a full size version). It charts all articles (including advertisements) in the Chicago Tribune that use the term "heartland," whether or not they are referring to the American Midwest, from 1849-2006. It is a rough measure, but serviceable.

The search seems to confirm the first part of my thesis, about the timing of "heartland" popularity. The term "heartland" rarely appeared in the Tribune in any form before the mid 1940s, and remained limited in use until the late 20th century. There were only 15 articles before 1940 (none of which seem relevant), and only 8 between 1940 and 1946. From 1946-1949, there were 28 articles (perhaps half about the midwest). From there, heartland becomes an ever more attractive (and diffuse) metaphor and label. There is a big jump in the decade of the 1980s, and then an apparent leveling off.

A combined search for "heartland" and "midwest" actually yields a more dramatic curve, although a much smaller volume of articles. Once again the big jump comes in the 1980s. In the 1970s only 46 articles or ads included both terms. In the 1980s, 240 did so. 431 during the 1990s.

Why? And what does it mean? Those are the subjects of my next post or posts. Until then, for the data-inclined I offer the following related charts to ponder:

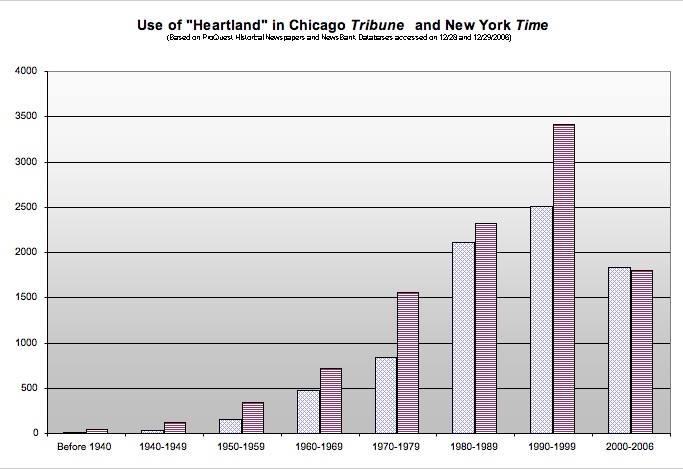

Use of "heartland" in the Tribune and the New York Times. Notice that the Times is way out ahead of the Tribune in the 1970s, but they are almost equal in the '90s. An example of cultural diffussion? Or just New Yorkers' love of the exotic other?